http://ssv.omeka.bucknell.edu/omeka/neatline/show/conservation-regions-in-susquehanna-country

Susquehanna Country took on a different role from many courses at Bucknell. It is grounded in the local history of the fertile Susquehanna valley with an emphasis on digital media as a mode of communication. Throughout the semester, the class looked at different digital mediums that are used to present information. These included Omeka Exhibits, podcasts, PowerPoint presentations, as well as others. However, forming my final research question called for the use of Neatline, which, despite having almost no prior experience with this feature of Omeka, ultimately serves as an excellent tool that improves the presentation of my findings.

After some preliminary research and a bit of revising, I managed to formulate the following research question: How do conservation efforts in Susquehanna Country differ according to historical context, as well as between projects involving regions defined as “native” vs. “settler” lands? With a large portion of the class (particularly in the first couple of months) focused on the interactions between Susquehanna country’s indigenous peoples and the European immigrants, selecting a topic that involves this aspect of class seemed like a logical approach. We had solid footing on the subject matter, with James Fenimore Cooper’s The Deerslayer serving as an excellent resource to compare with the history at Otstonwakin.

With an established research question, I considered how to present the exhibit digitally. Our WordPress blog sites are a great method of publishing findings and making them widely available through the internet, but the crux of this approach is that it lacks a visually interactive and engaging aspect. Comparing “native” and “settler” lands poses certain difficulties due to varying definitions of a region. European immigrants laid claim to any land they found, whereas many indigenous peoples had no concept of land ownership. These two platforms of culture existed together as overlay landscapes. With two distinct cultures in mind, I decided that presenting the history and conservation of these two types of landscapes demanded a representation of their proximity.

Consulting Reneé Carey at the Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy, I found a conservation easement located less than 10 miles from the site of Otstonwakin, the Logue-McMahon property. A bit of digging led me to some excellent informational resources provided by the NPC, as well as Lara Schmitt who actually owns the Logue-McMahon property. Working in admissions at Bucknell, Lara expressed a welcoming attitude toward my research of her conservation easement property. Interviewing with Lara not only provided me with valuable information regarding the history and current conservation efforts with her property, but recording the conversation and posting an excerpt on my final exhibit significantly increases the level of interactivity.

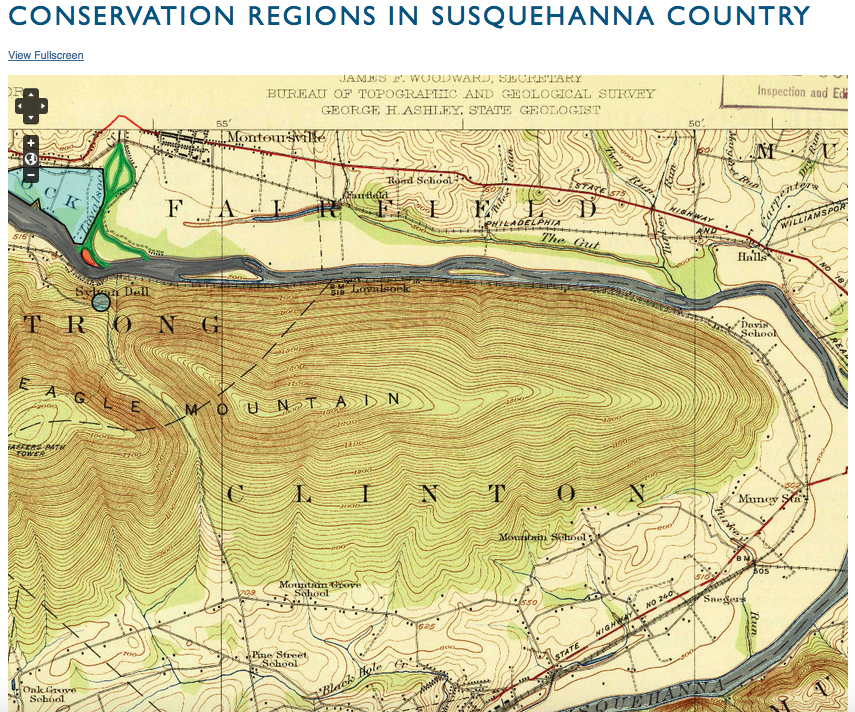

Engaging my audience remained a primary concern. Through personal experience, I’ve noticed the effects a well-designed website, in terms of both organization and interactive content, on individual interest and curiosity. Neatline enables the use of a background image, for which I chose a map of Milton that contains both conservation projects so I could help the audience better visualize the two sites. The historical presence of Otstonwakin and Port Penn existed simultaneously, but in different operational capacities. From here, it was necessary to provide the historical context of each location. A page on conservation would follow the pages on each site’s history.

I felt that a Neatline exhibit is a fun website to explore, which can be slightly distracting. As opposed to posting the majority of my textual content directly in pop-ups from interactive items on the map, I provide brief summaries and simple multimedia for the two conservation sites, as well as some other aspects on the map. This setup allows a user to jump around from one item to another, providing a preliminary glance at some of the features. Further reading requires the user to click on the “Read More on …” links which redirect to Omeka exhibits. Posting on these Omeka exhibits after the field trip to Otstonwakin early in the semester allowed me to see the value in the site’s ability to build a simple, but professional web exhibit. My first exhibit, Otstonwakin Village, influenced this aspect of my project, allowing me to improve these final exhibits through more in depth research, as well as utilization of photo galleries and YouTube video imports.

The audio from my interview of Lara Schmitt is one of the most engaging aspects of the site, as its immediacy has the ability to seriously grasp the attention of someone who has no experience with the history of the Susquehanna valley or conservation easement whatsoever. Because of this, I know it would have been ideal to interview Reneé Carey, my primary contact regarding the Otstonwakin village, as well. Logistically, I was unable to organize the interview, but her input and resources have contributed greatly to the information about the historical native village.

While I originally set out to explore differences in how agencies such as the NPC approach new conservation projects with regard to their native vs. settler historical context, I was slightly surprised by my findings. NPC’s regulation of Otstonwakin and the Logue-McMahon property are quite similar in concept; both require no further changes to be imposed on either land. The differences lie within the fact that Otstonwakin village retains not significant structures that require maintenance and protection, whereas the River House, lock house, and barn are regulated meticulously. As mentioned throughout the exhibit, the buildings on the Logue-McMahon property cannot be altered visually whatsoever. This mandates that period-paint and other materials must be used when maintenance is conducted on the house.

With regard to the conservation of the land at either sites, there are almost no differences. Both limit the land uses in terms of clear cutting and plowing, so as to protect the many artifacts buried just beneath the surface. The lands are left to return to their natural states. The previously drained wooded-wetland is left to become a marsh again, and Otstonwakin can see no further land impact either. The ultimate goal of conservation easements involves protecting the history of significant regions long into the future, and this is typically done my minimizing further effects on the site.

http://bucknell.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=975defb6021445c1a81adee5dc76c814

A region does not have to be specified by certain boundaries. It is the people and the culture that make a region a region. This is a central concept throughout Wendell Berry’s writing as he relates the people to the land they live on through ecosemiotics. For this project, I am focusing on my family’s heritage, specifically my mother’s side of the family. My mother’s parents have lived in Staten Island their entire lives, so I plan to concentrate my studies on the concept of what a region is and why people would choose to stay in a region. How do the themes of place and region relate to family lineages and what are some of the ethics associated with seeking information? By using ArcGIS as a tool for analysis, the concept of what defines a region and the ethics of looking and not looking will be evaluated using my own family tree and comparing it to ideas that MacGaffey, Marsh, Berry, and Scruton highlight in their writings.

While Janet MacGaffey’s Coal Dust on Your Feet focuses on the coal miners living in the Susquehanna area, there are many parallels between her writings and my family’s history. The family on my mother’s side is from Poland and Italy. In Italy, some of my family members were bread bakers, and they had very little money (see map slide 3). In Poland, my family worked in factories where they were also extremely poor (see map slide 1). Coming to the United States was an opportunity for my family to escape the rigid economic mobility of their respective home countries. Although the jobs that they had when they moved here were low paying and not very different from jobs they had prior to moving, they believed that the United States brought more opportunities than Europe would ever give them. According to Janet MacGaffey, there was, “intolerable oppression by an alien power” in Slavic countries and these people were able to fill, “the increasing demand for unskilled labor” in America (MacGaffey 14). The continually changing territories of Poland contributed to my family’s immigration to America as well (see map slide 1). It created an environment in which they did not wish to live, even if it was their home country. As for Italians, many intended on coming to the United States to make money for their family and then send it home. The unification of the north of Italy with the south in 1871 caused a lot of turmoil that was occurring in Italy around the time of my great great grandparents immigration to America (see map slide 3). This led to many Italians leaving the country in the early 1900s, including my great great grandparents. My relatives had no intention of returning, though, which contrasts with some of the families that originally left Italy according to MacGaffey.

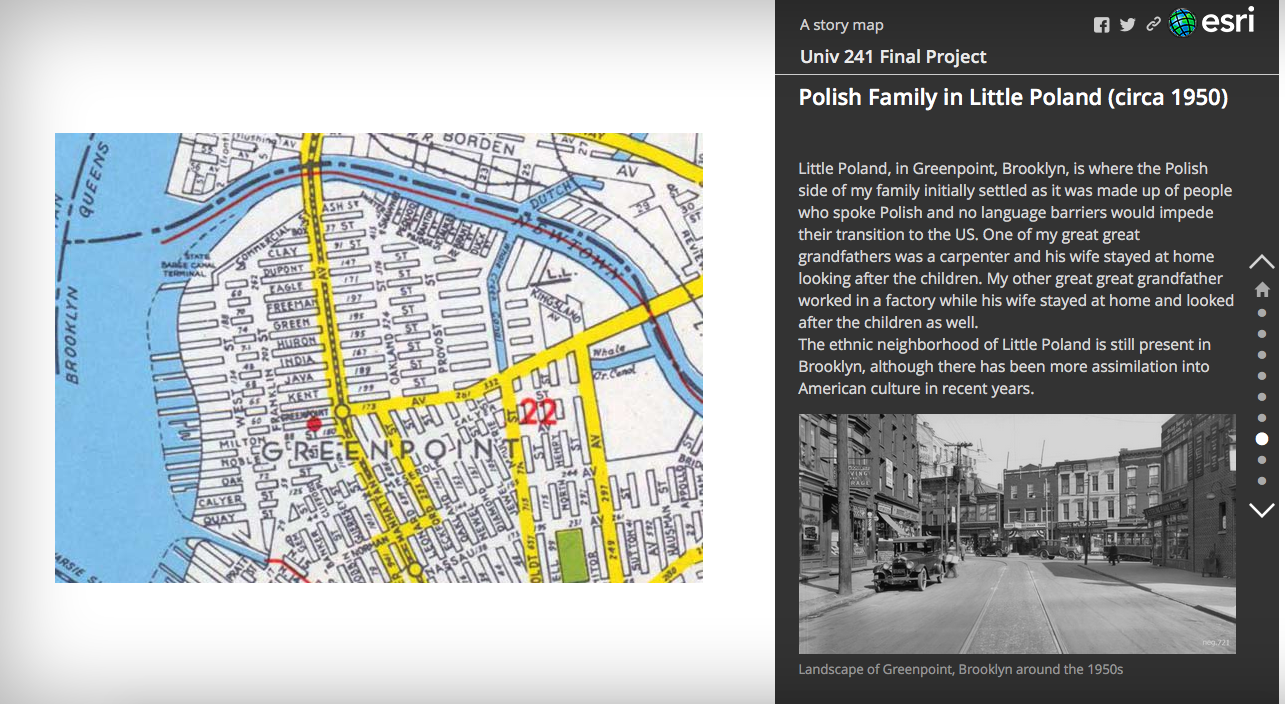

Ben Marsh’s Continuity and Decline in the Anthracite Towns of Pennsylvania illustrates the feelings people have for a place. When my relatives first arrived in the United States by going through Ellis Island in the early 1900s (see map slide 5), the Italian side of my family settled in Little Italy, Manhattan (see map slide 6) while the Polish side settled in Little Poland, or Greenpoint, Brooklyn (see map slide 7). These ethnic neighborhoods were pre-established before my family’s arrival and they allowed for an easier assimilation to American culture along with minimal language barriers in their home lives. After living in Manhattan and Brooklyn for a short period of time, both sides of my family knew enough English to move to Staten Island around 1950, which is where my grandparents still live today (see map slide 8). Although the homes they have lived in have changed, my grandparents were able to save a lot of the money they made throughout their lives and now live comfortably in a home in Staten Island. They have the ability to live elsewhere, however they choose to stay because they have oikophilia for the area they have known all of their lives, which is what prevents them from permanently leaving. Marsh highlights the sentimentality that people have for a place when he states, “Place is Janus-like in time, both product of the past and producer of the future, and it is therefore a part of the inertia within society whereby the past forms the future” (Marsh 338). It is the history of a place within a region that provides such a powerful incentive for my family to stay in the region that is Staten Island. The region is a meaningful landscape to my grandparents and others who have lived there most of their live. Once people have built their lives and assimilated to the culture of a place it becomes a region rather than just a place or location where they live. The ecosemiosphere of the region is important as it connects the culture and nature that is in Staten Island. Additionally, Staten Island is the least exploited of the burroughs, with it having around 170 parks available for residents to use. This aspect of the island allows for their to be a deeper connection of the people to the land. For instance, Wolfe’s Pond Park is a beach area a few blocks away from my grandparents home. Although people do not swim in the New York water, they still enjoy the landscape of the park and beach. For these reasons and many others, my grandparents have stayed in Staten Island their entire lives and do not wish to permanently leave anytime soon.

There were a few ethical dilemmas that I encountered when doing some initial research with my family. The first time this came about was when I spoke with my father about his family. He knew little about his mother, who was Irish, which is interesting as there were most likely many aspects of her family history that she was not comfortable sharing with my father when he was younger. It may be connected with the Great Potato Famine but she did not speak about it so we cannot know for sure. Additionally, my grandfather knew very little about his grandmother, including her name. He would only call her Babcia, which means grandmother in Polish. Both my father and grandfather had sought information that was not welcomed for them to seek. In this sense, there are ethical dilemmas that arise when seeking information. If the information is staying amongst family members it may still be ethical, however distributing the information or making it public causes ethical dilemmas. The distribution of their information may have led to hesitation about sharing their stories, perhaps leading to decontextualization of the information that they share. This also relates to the way in which museums objectify other cultures by making art of everyday objects. I did not feel as though I was breaching any ethical boundaries during my research for the project most likely because those who I spoke with are generally open about speaking about our family’s history.

The main tie of my family back to Susquehanna Country is my being here (see map slide 9). Even though some family members have lived in one place for all of their lives, I have moved from Pennsylvania to New Jersey and back to Pennsylvania. Perhaps part of the reason that I returned to Pennsylvania is the sentimentality I feel for the area, with it being my childhood home. The region that is Susquehanna country is one that I had known for thirteen years of my life when I lived in Hershey, Pennsylvania. My father worked in Harrisburg where the Susquehanna river runs through. It seems fitting that I would return to another part of the region where the Susquehanna runs as well. Wendell Berry accurately describes my feelings toward the land in Pennsylvania when he says, “We see the likelihood that our surroundings, from our clothes to our countryside, are the products of our inward life–our spirit, our vision–as much as they are products of nature and work” (Berry 14). Berry sees the landscape we live in to be an integral part of our lives, as do I.

There is a lot of work that can be done to improve the way in which people treat land, especially in urban areas. In the region that makes up Susquehanna country, there is a tendency of people to treat the land they live on in a much more respectable way. It is true that in Staten Island there are some resemblances of “downtown areas of American cities…and the trash scattered all around them” (Scruton 257). However, perhaps it is a call to attention that there must be more time put into taking care of lands in urban cities as they are taken care of in more rural areas of the country, as seen in the Susquehanna region. Something that I noticed while interviewing my grandparents was the impact that the Verrazano Bridge had on the influx of people in Staten Island. It provided a connection between Brooklyn and Staten Island that was not previously there and it increased the population size immensely. Through our building of bridges and buildings we increase the positive feedback occurring on the environment, and although we build on suburban and rural areas, the impact we have on urban areas is much more intense than the suburban.

Overall, ArcGIS has been an effective tool in allowing for there to be a spacial arrangement of the areas my family has lived. It does a nice job of demonstrating the transatlantic cross of my family from Europe to America. The story map has allowed for connections to be made between my family lineage and the concept of what defines a region. It is evident that a region is defined by those who inhabit it and the relation that people have with a region strongly connects them to their culture and land.

Works Cited:

Berry, Wendell. The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1977. Print.

“Borough Trends & Insights.” NYCEDC. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 May 2016.

Kemeny, Matthew. “Harrisburg River Rescue, Firefighters Rescue Men Stuck in Pontoon Boat on Susquehanna River.” PennLive.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

“Lect 7.” Lect 7. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 May 2016.

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Manhattan, V.

1, Plate No. 47 [Map bounded by Grand St., Centre St., White St., Broadway]” The

New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1884- – 1903.

“LOST STREETS OF GREENPOINT | | Forgotten New York.” Forgotten New York. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 May 2016.

MacGaffey, Janet. Coal Dust on Your Feet: The Rise, Decline, and Restoration of an

Anthracite Mining Town. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

Marsh, Ben. “Continuity and Decline in the Anthracite Towns of Pennsylvania.” (n.d.): n. Pag. Web.

“NSSE – National Survey of Student Engagement.” NSSE Institute 2015 Bucknell Workshop.

N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

“Wolfe’s Pond Park.” Nycgo.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

“Old Brooklyn Photos Pictures Books.” BrooklynPix.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

“Passenger List, Cunard Line, R.M.S. Lusitania, 6 June 1908.” Sitewide RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

Scruton, Roger. Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously about the Planet. London: Atlantic, Print.

Sea, C., and Balti. (n.d.): n. pag. Web.

“Staten Island.” Old Staten Island. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.